- Home

- Gabrielle Mathieu

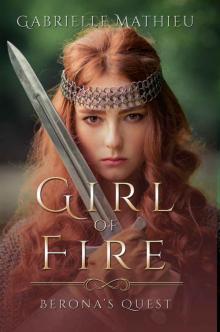

Girl of Fire Page 2

Girl of Fire Read online

Page 2

The Lighthouse Keeper reached out, grabbed the hem of Luca’s silk robe. “I beg of you. Track her down, even if you have to travel all through the Heartland. No one should have to lose a child like that.”

Luca frowned. Now the costly silk would be stained with salt and mud. The Mercantile Advisor caught Luca’s eye and then looked meaningfully at the shore, where the Duke had begun to pace.

Luca reached over and took a gold coin from the bag that Samu always carried for him. “We thank you and yours for your service.” He tried to hand it to the man, who stayed kneeling on the deck. Nula finally took it.

As the Duke’s man helped Luca down the ladder into the rocking boat, the Lighthouse Keeper’s voice followed him. “You think gold can bring my son back, Sire?”

CHAPTER 3

Berona

I hurried back to our home. No hoarse barking greeted me. Father must have already left for the day’s work with our shaggy farm dog. I had to find him. He’d know what to do. When wolves had prowled too near one hard winter, he’d led the villagers, armed with his strong bow and sharp hunting knife. He’d brought back a wolf pelt to keep my mother warm during the snows.

Before seeking him out, I needed to attend to my appearance. I stank of blood and sweat, and my long red hair hung tangled down my back. We were not rich, but he demanded his daughters carry themselves with pride.

I found a full pail by the small stone outhouse and scrubbed with some rags and Castile soap, then raced inside to find a clean tunic. Dedi danced up to me, bright eyes shiny.

“Another suitor sent packing last night?” Dedi was fourteen and fascinated by my prospects.

“I didn’t send Ged packing,” I pointed out sourly.

“You didn’t make a single joke. You didn’t even smile. Though Ged is tall, and he’s only thirty, and he has twenty sheep. He could dress you in velvets and furs…” She twirled.

“Twenty sheep will hardly enable him to dress me in furs, even if I cared about that.” I checked around to make sure Mother was not watching before I imitated his stiff gait and rigid posture. “He won’t dance with me. I’m sure of it.” I slipped off my torn tunic and slipped on the clean one.

“You don’t even know how to dance.”

“That’s why I’d like a husband who could teach me.” I grabbed my comb and yanked at my curls, patting them smooth with some beeswax.

“Your tunic is so muddy.” Dedi frowned. “I’ll wash it for you in the river if you’ll take the goats today. The black one always tries to bite me.”

My heart pounded. I whirled on her. “You do not go to the river, understand? Stay home.”

At that moment Mother ran in, disheveled. “So you heard too, Berona?”

I paused in the middle of putting on my boots. Had the Demon attacked someone else?

She threw her arms around me. “Rheyna’s vanished. She never came home.”

My mouth became so dry I could hardly get out the words. Rheyna was the daughter of the local midwife, a widow who lived nearby. “Did she go to the river?”

“No. Her mother saw her talking to a man. They were by the King’s Road. She thought nothing more of it; perhaps a stranger asking for directions? But then Rheyna never came home.”

So a man, not a demon. Unless my demon could turn into a man. But in the stories the minor demons always turned into young beauties, luring good husbands away from their families, or whispering foul lies into the ears of foreign kings. The malevolent Water Demon, the worst one, could travel in storms, and commanded the terrible Elementals. Thank Amur, the Priest-King slew her with his magic sword, ending the Great War.

My mother drew me tight, so tight I almost couldn’t breathe. “I could not bear to lose a child. Both of you stay near me today.”

I had been about to tell her of the nightmarish creature, but the worry etched on her face stopped me. I supposed losing me to a sinister stranger would be worse than sending me to a stern husband. Amur forbid she find out about the Demon. I didn’t want to add to her burdens. I removed her arms gently from my waist. “I should find Father. He’ll want to gather the men together to look for her.”

My mother’s kin, descendants of the wealthy founders of the village, chose not to have anything to do with us. My mother had married the descendant of their serfs after all, even if he bought his own patch of land. But the rest of the village held together, and my father was esteemed for his tenacity and common sense.

As I saw her waver, I grabbed my slingshot. “I can’t stay locked up inside. I’ll be with safe with Father.”

I was out the door before she could protest.

* * *

I found him among the grapes, as I thought I would, his hand curled tenderly around a wayward vine, pushing it back onto the trellis. The grapes were still small and sour, little globes of green trembling as he moved the branch. I thought of the harvest, when the grapes would be plump and ripe, their acrid fruity smell flashing through the air, their skins close to splitting. If they were not harvested, they would rot on the vine. Perhaps Father believed I too would rot, if I was not given away.

He lifted his head in acknowledgment of my presence. He had dark brown eyes, totally unlike mine, eyes that were flat and hard until he beheld my mother, her curls demure under her goodwife’s cap. It was strange to think that his grandfather had been my grandmother’s servant.

“Last evening did not go well,” he accused. “Ged traveled half a day to meet you, and it was plain you thought him unsuitable.”

This was not what I had come for, but I knew better than to interrupt.

“You will be eighteen in a week, girl, past time to start your own family. People are beginning to talk.”

Our argument was so habitual that I could not restrain my answer. “Why can’t I just wait? I’m strong. I help out here.”

“Dedi cannot marry until you are gone.” Then he added something he’d never said before. “Your blood runs hot like your mother’s. If I do not give you over to the care of a husband, with your good looks you will cause trouble.”

I pulled my shawl closer, embarrassed about my blossoming body. Why did Father believe I would entice men to sin? I spent all my spare time alone, climbing the mountains in search of wild places where I could swim in clear sparkling streams and dry myself next to a small fire before I returned home with a basket of herbs, or a rabbit for the cooking pot. Our house appeared small and dark after these carefree days spent with the sparkle of sunshine and the flutter of forest in the breeze. Only the touch of my mother’s hand brought me back, reminding me that those I loved were here.

Here to be preyed on by a demon.

I crouched down to yank out a weed and let a few moments pass so his temper could subside. “Have you heard of any trouble?”

“Like what? A child that won’t listen?”

“Witches. Ghosts…or even demons,” I said, ignoring the reprimand.

“What fanciful questions you ask. Life is simple here. Grow grapes. Harvest them. Drink them.”

I nodded, beginning to sweat. I must be the only girl she’d visited. What had I done to attract her attention? Had the Goddess sent her to punish me?

His voice was dry. “You didn’t come here to pull weeds.”

“There’s trouble about. Rheyna’s gone missing, after being seen talking to a stranger, but there’s worse. Much worse.”

He rocked back on his haunches, the vine forgotten. “What?”

Now that I’d started, questions spun out of my mouth. “How many kinds of demons are there? Who can kill them? Only an Intercessor? Could you kill one?”

He got up slowly, brushing the dirt from his homespun shirt. His eyes held mine. “There was the Water Demon, but the Priest-King put her to the sword. The same Priest-King who imprisoned the Elementals.”

I nodded. The old woman who took care of Amur’s shrine in the village had told us. “And what of the other demons?” My voice was hollow.

“What of t

hem?”

“Why would they seek out mortals?”

He seized the soft flesh of my arm, pinching it in his calloused hand. “What have you done?”

My throat closed up at the thought of her. “She came for me by the river,” I whispered. “She sought me out. She threatened us…”

His slap ended my words. He had never hit me before, though we fought more and more. My cheek stung. He had not held back. My questions died in my throat.

“Your mother’s family set her aside,” he said. “And why is that?”

Was it not because she married my father, the grandson of their field workers? I thought that was not what he wanted to hear. I pressed my lips together.

He chose not to answer his own question. Instead he said, “I did not want to have a family so soon. I scrimped and saved to buy this miserable patch of dirt. When you came along, I tried to love you, because I loved your mother. But I will not let you drag us down.”

“What about the Demon?” I said.

His face came close to mine, a spray of spittle misting my face as he enunciated every word. “There is no demon. Because what kind of a girl would see a demon? Only one whose mother is cursed. Do you want to bring on a visit from the Intercessor?”

I took a step away from him, blinking away my tears, and touching my cheek. It would swell soon. I had to make a poultice.

* * *

I found some boneset and chewed it up, then slathered it on my face. If I went back home now, Mother wouldn’t let me out the door again. Instead, I chose some round heavy stones for my slingshot and headed to a grassy open ridge directly over the river. The sun shone and cornflowers shot blue out of the tall grass. Bees cuddled into the pink of clover blossoms. I felt safe in the open meadow.

The Demon had not left the water to chase after me. Perhaps she could not. I checked for tracks on the muddy bank.

I saw some. Just not hers.

Fresh boot prints. My father’s.

* * *

When she said destroy, I had not understood. What did it mean to destroy? Did it mean to render flesh, snap bones? Or did it mean to curdle thoughts, nurture suspicion, sharpen anger into hatred?

I needed someone to fight her. But whom? I could not trust Father. The Intercessor and his Chosen? The old woman from the village shrine would inform them of my prank, replacing the statue of Amur. I had not thought it desecration when I’d done it. It was only that she’d said Amur gathered us all to her bosom to preserve us, like a squirrel harvesting nuts, so Dedi and I brought an actual squirrel, discovered frozen in the snow, and set it up on the altar. No one else laughed.

So not the Intercessor. As Father said, what kind of girl sees a demon?

My mother did not leave the house without her goodwife’s cap on and her eyes cast down. My uncles would sooner gallop their fine steeds through the village green than acknowledge their sister’s lowborn family.

I looked down at my slingshot. I had brought down mallards and hares, but I doubted it would be much use against a demon. If only we could all leave, go to a faraway place, start over. Father had called our farm a piece of dirt, and his puzzling comment about my mother’s hot blood made me wonder if the villagers gossiped about us.

Either we fled or I found a way to fight her. I doubted I could convince Father to leave.

Last fall, when Dedi had pleurisy, we’d walked to the nearest town to fetch herbs from a healer. There had been a real bladesmith there. While Father described Dedi’s pain, I’d been drawn down the street by the smoky smell and the song of the bladesmith’s hammer. His swords cost dearly, but they were well made, honed to a sharp edge.

The quickest way there was a day’s journey on a poorly marked track over the mountain into another valley, and this time I would be without Father. But I didn’t mind. As a lone woman, I would be safer in the wilderness than on the King’s Road. The wild places sang out my name, the mountains with their lofty peaks, and dark leaf-scented forests with their hidden glades of ferns. It did not mean that I did not love carding wool with Mother as she spun and sang, or pounding the kernels of maize into meal with Dedi. I was always glad to be warm and safe with them—in the evenings, or when the snow piled up outside.

Visiting the bladesmith would be an adventure. With Rheyna’s disappearance, I could undertake the trip knowing that my sister would be kept safely inside during my absence.

There were only two flaws with the plan.

Swords cost lots of silver. And even if I bought one, I had no idea how to use it. But I would tackle one obstacle at a time.

* * *

Last fall, shortly before our trip and hoping to avoid chores, I’d climbed a leafy oak tree and dozed there, daydreaming about a husband. He would be a gorgeous man, nimble on his feet and deft with his words. His lips would brush mine, and then?

The clang of a shovel woke me. I stayed quiet. Scarcely a few feet under me, Father labored, digging up a chest, taking out something, and then burying it again. The Priest-King was building a new temple for Amur in the capital, and we were scarcely the only ones that kept a little hidden from the Tax Assessor.

Now I planned to empty that chest. It was for the good of my family, and it would be Father’s own fault that I was forced to rob him.

The buried chest was very close to the path the goats took to the water. I washed the boneset from my face, brushed a bee from my shift, and went to their pen. Their yellow eyes gleamed, and their rank smell hung in the air. I loved the goats. Not one had ever nipped me, though they could be ill-tempered with others. When I unlatched the gate, they sprang out, tumbling past me and heading toward the river.

I followed, slowed down by the shovel and covered pail I carried. I hoped there would be enough silver to at least fill the bottom. The sun beat down, the pleasant scent of warm loam filling the air. Crickets chirped in the meadow of cornflowers, yarrow, and yellow daisies. I caught the sound of the river, light and tinkling. I gave it a wary look. I was relieved to note that the current flowed toward the sea again.

The goats would find their own way down to the water. I stopped in the maize field, decorated in the middle with a mound of rocks. I saw a stray stone, perhaps kicked to the side by one of our frisky goats, and carried it carefully into the center, murmuring quick words of thanks to Amur. The circular field was the breast of Amur—the stones the nipple—and the harvest the bounty that fed her children. Without her nourishment, we would fail. Wilderness would undo all we had accomplished.

I’d been told often enough. The Heartland would become a wasteland without the guiding hand of the Goddess. That was why we submitted to Amur’s Chosen and the Intercessors, with their list of admonishments. They guaranteed the harvests—if we could guarantee our good conduct.

Now I was preparing to do one of the worst things an unmarried woman could do. I would set off alone, without a chaperone to see to my chastity. And I would do so with stolen silver, silver my family would count on in an emergency.

But wasn’t the Demon in the river an emergency as well? I wondered how she had set Father against me. I could not believe he would converse with her. Could she influence his thoughts just through proximity?

As I dug, I went over the route in my mind. If I left early the next morning, I could be in the town before sunset. The healer would likely give me a cot for the night, and the next morning I would visit the bladesmith. The shovel hit something hard. I fell on my hands and knees and grubbed at the dirt.

I lifted the lid. Perhaps there would be enough silver to pay for a sword and a lesson. Or two.

I rocked back on my heels, mouth open in shock. Only two bronze pieces. Father had used all our savings on medicine for Dedi.

Hard on that realization followed another. Mother had told me often enough I was beautiful. I’d understood men would pay a high bridal price to have such a wife, even if she was stubborn as a goat. My parents would not force me to marry. Yet they must have hoped I would make a good match.

> Now we had a bigger problem than finding a suitable husband.

A shadow fell. I slammed the lid down and rose to my feet.

A Mannite. This one wore the Yellow Robe. More bad fortune.

I was alone, just as the Demon foretold. Here was one of those dreaded men. A heretic. A magician. A thief of young women. He’d find me harder prey than Rheyna.

The man stood quietly, ignoring the uncovered chest. At least he wasn’t here to rob us. I took a few steps back and raised the shovel shoulder-height, ready to swing.

When he spoke, his voice was low and pleasant. “Merry meet.”

I was expecting a curse, or at least some sort of exotic greeting. All of us country folk said, “Merry meet.”

I didn’t answer. I was caught up in the dazzle of his yellow cloak. It reminded me of good things: rock daffodils, thick, nourishing egg yolks, the marigolds in our vegetable garden. I had been taught to fear that color in a man’s cloak, but it was such a happy color, a color that might drive away dark. Yet he’d stolen Rheyna. The Priest-King said the Mannites would poison your mind and steal your faith.

When I pulled myself to my full height, I was almost as tall as he was. “Father will be getting the other men together. If you free the girl you stole and flee, I’ll tell them you’ve gone.” I leaned in for emphasis. “If you’re lucky, they won’t track you with the dogs.”

“The girl I stole?” He looked offended.

“Rheyna. The midwife’s daughter.”

“Her presence is an inconvenience, but she’s desperate. If I don’t help her, who will?”

I remembered her ragged clothing and thin face. Father had brought part of his kills over to her mother most of the winter. No one used the midwife anymore since she’d lost the favor of the local Intercessor. “Rheyna wanted to go with you?”

Girl of Fire

Girl of Fire